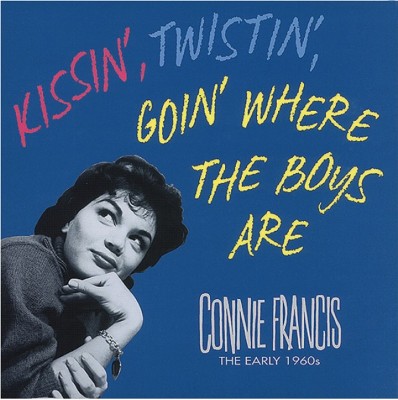

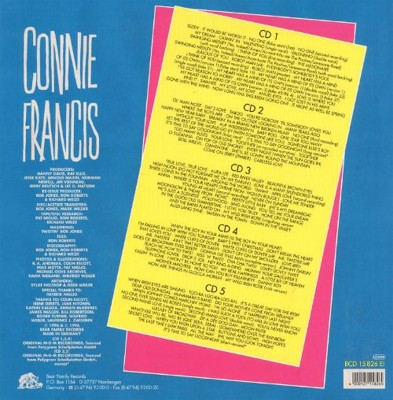

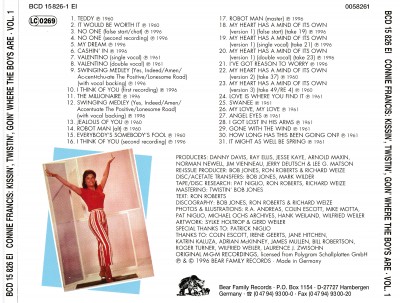

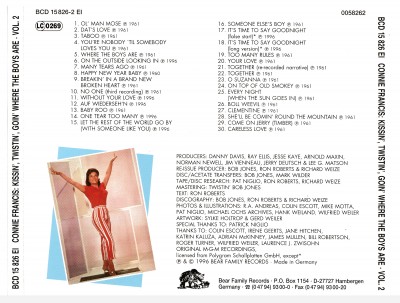

Bear Family BCD 15826 EI

CONNIE FRANCIS: KISSIN’, TWISTIN’, GOIN’ WHERE THE BOYS ARE

If, for Connie Francis, the Fifties had indeed proved to be “Fabulous” then, depending on which side of the world her recording achievements were being assessed, the Sixties could just as appropriately be deemed “Sensational” or “Swinging”. Fêted in 1959 as the queen of pop music in every major English-speaking market, hers was an unparalleled assault on the best-selling charts in these territories by a female singer that would be matched, and eventually surpassed, by sales performances of recordings in as many as 13 different languages on all five continents in the new decade.

Unlike Bear Family's first CD collection of Connie's English language recordings (BCD 15616 EI `White Sox, Pink Lipstick...and Stupid Cupid’) which embraced her entire Fifties repertoire, this follow-up package, containing a similar number of performances, “merely” covers the period January 1960 to April 1962, so prolific had been her output. It opens with selections recorded on January 25, 1960 at Radio Recorders, Hollywood; one of two sessions undertaken by Connie during “free” afternoons while appearing at the prestigious Cloisters nightspot. The first of these was Teddy, written for her by fellow international hitmaker Paul Anka as a tribute to her friend, former Three Chuckles member Teddy Randazzo.

The choice of a boy’s name title had been prompted by her million-selling 1959 smash Frankie, with which it shared a coincidental pedigree. Frankie had also been written by a fellow charts performer, Neil Sedaka, and had allegedly been in honor of Frankie Avalon, one of the artists to appear in the movie `Jamboree’ for which Connie had supplied the singing voice of actress Freda Holloway. Randazzo had been the star of another rock’n’roll picture, `Rock, Rock, Rock!’, that had seen her perform similar duties for its leading lady Tuesday Weld. Another shared factor was that both titles were first released as B-sides to million-selling singles (Frankie was the flip to Lipstick On Your Collar), but went on to achieve gold disc-winning chart status in their own right.

Teddy, which had been coupled with Mama, a track culled from Connie's November 1959 album release `Connie Francis Sings Italian Favorites’ (her foreign language material is projected for future Bear Family release) peaked at #17 in the US charts. The success of her first recording of the Sixties proved to be bittersweet. She and Anka had agreed on a 50-50 publishing deal for the tune before release and, following an appearance on US TV's `Perry Como Show’, there was public demand for Mama to be issued on a single. Paul was touring in Europe at the time and Connie contacted his father to appraise him of the publishing agreement she had with Anka Jr, and the intention to couple the track with Mama. Since Anka Sr confirmed that any deal made with his son would be honoured, she was stunned when, on his return Paul denied any such publishing arrangement. Connie was herself about to undertake personal appearances in England, and gave out the order that in any country where Mama was scheduled for release, it should not be coupled with Teddy. The “blacking” of Teddy had a direct effect on a second LP collection of US chart entries, `More Greatest Hits’, on which only first pressings featured the Anka song and all subsequent editions carried Valentino in its place.

Valentino, cut at Connie's second Radio Recorders session on January 27, with the hitherto unreleased Cashin’ In, Swinging Medley and I Think Of You, had been coupled with It Would Be Worth It from the earlier date on a British single. Stemming from that first session is another previously unissued track No One, a reworking of the Doc Pomus/Mort Shuman song originally recorded by her in October 16, 1959, and the teen angst-ridden My Dream. She clearly had faith in several elements of these sessions since, over the next two years, she would record yet another version of No One, make Hank Hunter, the composer of Cashin’ In, one of her preferred songwriters, and newly record Swinging Medley (retaining that track's arranger, Dick Wess, for future use) and I Think Of You.

One month later, despite these freshly cut titles “in the can”, and a host of pre-1960 performances still awaiting release, she contacted her favorite lyricist Howie Greenfield (Stupid Cupid, Fallin’, Frankie - all written with Neil Sedaka). Recollects Connie: “I had been on a promotion trip to Germany and couldn't believe the size of their market. I also discovered that they like country music so I called Howie and asked: `Did you write that country tune for me yet...?’ `Jack [(Keller) - Neil Sedaka was away on tour] and I wrote it together.’ `...What's it called?’ `It's called `Everybody's Somebody's Fool’.’ `Love it! Hit title!’ When I saw him next he played me this LaVern Baker-type blues number. `It's great,’ I said, `but it's not what I want. I want it for Germany. It needs to be more regimented, more precise.’ `Like what?’ Howie asked, '`Deutschland Uber Alles’?’ I told him not to be cute. `It needs to be more up-tempo, like `Heartaches By The Number’ .’ [A 1959 million-seller for Guy Mitchell.] They did as I asked and it worked very well.”

Soon after first meeting Connie in 1958, Greenfield and Sedaka had teased her about the diary into which she would constantly jot down her thoughts and views. The banter led to Neil writing a song about it - The Diary, with which he scored his own first vocal success. Thanks to those diaries and the notes she kept, Connie has a story to relate about an extraordinary number of recordings.

Father George (Franconero), whom she laughingly accuses of “dumping monstrous projects in my lap” - like getting his daughter, under threat of termination of recording contract, to cut a triple-beat version of Who’s Sorry Now? and then, on making it to the pop charts, persuading her to record that LP of `Italian Favorites’, which gave Connie her first album chart entry week-ending February 8 (it stayed in the charts 81 weeks peaking at #4) reciprocates with “My Connie, she wouldn’t know a hit if she ran over it with her car!”

Laughs Connie: “I knew I had a hit with `Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool’ and one day my father came home from Melody Mike’s Record Shop in Newark with this old Italian song `Jealous Of You’ and says to me: `Here, throw this song on the other side of that country thing. You need a follow-up to `Mama’.’. `What is it?’ ``Jealous Of You’.’ ‘Where’d you get it?’ ‘Down at Melody Mike’s’ ‘So what kind of a song is it?’ ‘Italian.’ ‘Italian!...What a shock!’ So I did his dumb song.”

On April 2, 1960 Connie became the first recipient of the “Best Selling Female Vocalist” trophy at the launch of the National Association of Record Merchandiser (NARM) awards. Five days later she undertook a two-part seven-hour recording session at New York’s Olmstead Studio at which she recorded that “dumb song” and, in the early hours of April 8, completed Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool.

Recalls Connie: “I grabbed Howie Greenfield and shouted `It’s a smash! I knew it as soon as I added the organ!’ I gave arranger Joe Sherman a hug, kissed engineer Val Valentin on the forehead, then noticed Arnold Maxin, the President of MGM Records. [Also credited as Producer of the session.] `You’re not serious?’ he asked. `Not serious about what?‘ `About releasing this...`Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool’?’ `Why not?...It’s a monster.’”

In Maxin’s opinion, the monster hit was the first recording of that session, the Greenfield-Barry Mann composition The Millionaire, for which, on completion, Connie was no longer enthusiastic. He sought support from George Franconero and Howie, but Connie’s father was a country fan and in favor of Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool, and Greenfield “didn’t care either way” since he was assured of songwriter royalties whatever the decision. In her 1983 autobiography “Who’s Sorry Now?”, Connie revealed that at one stage she asked Maxin to confirm that under the terms of her contract she was allowed to pick her own releases, upon receipt of which she declared “Okay, then, that’s it! `Everybody’s’ is the A side, `Jealous’ is the B side!”

Her contract, renewed in 1958, was without equal in the music business. “I don’t think it has been duplicated since. It allowed me to record wherever I wanted, whatever country, whatever arrangers, whatever songs, whatever engineer, musicians - and never release some of the product if I didn’t like it. I mean, isn’t that silly...I could have really bankrupted the company if I just decided I didn’t want to release anything, but that’s exactly what that contract said.” Emphasising the unique quality of her contract, which extended beyond the realms of the actual recordings, she adds: “I never paid for anything. I was even allowed to send in the bills for the gowns that I needed for album covers. MGM paid for every photographic session - and I got to keep the photos! I didn’t abuse it [the contract]...I tried to release even the garbage so that I wouldn’t just be recording and not releasing stuff. Some of it was so horrendous that I just couldn’t...like `The Millionaire’.” She laughs as she recalls the day she thought otherwise: “I remember the day I brought my father `The Millionaire’. I said: `Daddy did you hear this great Barry Mann song `The Millionaire’?’ He said `I don’t care if Chopin wrote it - it stinks!’”

“Stinker” or “Monster”, issued for the first time from that dramatic April 7 session is The Millionaire as well as a second recording of Swinging Medley. Feared lost, however, is No Other One, for which only a master number exists. [See Discography opus number 177.] The final April ’60 track, Robot Man, co-written by George Goehring who had earlier collaborated on Lipstick On Your Collar, has, in Connie’s opinion, “got to be the dumbest song I ever recorded. But when we pulled `Teddy’ out of Britain and put `Robot Man’ on the flip of `Mama’ instead, we had a number one double-sided hit.”

Gold status for Mama and chart action for `Italian Favorites’ brought a need for further material in similar vein, and a return to the London Abbey Road studios where, between May 12 and May 19, she concurrently recorded 15 Italian titles, 15 Spanish and 13 in Yiddish and Hebrew for use on collections of `More Italian Favorites’, `Spanish & Latin American Favorites’ and `Jewish Favorites’. She also took time out from the marathon sessions to appear on `Sunday Night at the London Palladium’ (a British TV variety broadcast, similar in style and content to the US `Ed Sullivan Show’), where she included both Mama and Robot Man in her four-song performance, and remained in town to see the titles enter the charts at #15 just five days later. She returned home to Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool becoming her first national #1 hit (#2 R&B, #24 Country) and Jealous Of You peaking at #17, topping the New York charts in the process. Within weeks of release in Italy, father George’s Melody Mike find became that country’s all-time best-seller.

Connie, however, would not rest until she met with similar success in Germany. An illustration of her determination is that, following a New York session on June 14, at which she cut a second (unreleased until now) version of I Think Of You, and “unissued/lost” work on Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool and Robot Man [See Discography opus numbers 180 and 182], she flew to Hollywood to begin work on her film début in ‘Where The Boys Are’. Within days of her arrival in Tinseltown, she had solicited the help of a Berlitz teacher and was back at the Radio Recorders studio, cutting a German language version of Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool (Die Liebe Ist Ein Seltsames Spiel).

From the outset, it was only Connie Francis who wanted that disc released: Arnold Maxin had described the venture as “a death wish - career suicide!”; and German MGM licensees, Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft (DGG) considered it “embarrassing” and likely to ruin her German career. But, DGG liked the song, and marketed five different versions of it by local artists. It was against such a background that Connie acquitted herself admirably in a comedy movie role, first angry and then compromising with DGG on permitting the entire opening refrain of Die Liebe... to be excised (they had complained it was unintelligible!), and finally vindicated when the track became Germany’s biggest-ever seller by a non-local artist and the Sedaka-Greenfield song the world’s #1 seller of the year.

Although Everybody's Somebody's Fool scored more heavily in the Country chart through an Ernest Tubb version, Connie was keen to maintain what inroad she had made, and turned to Howie and Jack Keller. On hearing the title of the suggested follow-up she recalls part of a late-night conversation: “`Whoa Howie! Run that by me one more time.’ ``My Heart Has A Mind Of Its Own`.` ``My Heart Has A Mind Of Its Own`? Love it! Hit title!' With a title like that, how could it lose? Sometimes, hearing the title was all it took for me to know it would be a hit...like `Lipstick On Your Collar’, for instance.”

Getting the song “in the can” was not so simple, and took eight hours of Radio Recorders studio time spread over three sessions on July 9, 25 and 31, and a total of 49 takes before completion. Although there were a high number of false starts, an example of which has been included in the collection, there exists an extraordinary number of complete different recordings. At both the July 9 and July 25 sessions, the proceedings were live and a successful take dependant upon the acceptable blending of artist, musicians and engineer, giving rise to fluctuations in the running lengths of performances.

The July 9 session produced complete takes 20 and 21, each of which consists of a single vocal. To the Take 20 vocal Connie added a harmony voice, the second attempt at which (take 23) produced the first master on which she is to be heard vocally double-tracking throughout. Both these takes are released for the first time on this collection. On July 25 she cut the previously unissued I've Got Reason To Worry, before continuing with My Heart Has A Mind Of Its Own. At this session, take numbers picked up from where those of July 9 had left off, and she completed take 37 which forms the version most widely released. Complicating matters for the completist is the recording date held on July 31, which studio sheets indicate as being one for overdub purposes only. At this session take 49 produced a version (identified also on studio sheets, as “Re-4”) that appears to be the one originally selected but then withdrawn in favor of take 37. Confusingly, both takes 37 and 49 have been used on different pressings of US single MGM K 12923!

Whichever the pressing, My Heart Has A Mind Of Its Own made Connie the first female vocalist to have back to back No.1s, and in Britain qualified for a silver disc (the local equivalent of a gold disc) based on 250,000 advance sales alone! It was joined in the charts by the flip, Malagueña (it reached #42), culled from her new album release `Connie Francis Sings Spanish & Latin American Favorites’.

Several times during her early career, Connie was either influenced, impressed or guided by her first real love, Bobby Darin. “He was a genius” she emphatically declares, “a one-of-a-kind kind of person. He was dynamic, extremely brilliant, avante garde and totally so much ahead of his time. In retrospect, I remember listening for hours to race music long before it was pop music. Bobby would say `The blues is the future of pop music - it’s still waiting in the wings. He had a feel for doing white songs in a black style that was absolutely appealing. He really did see a lot of things that were going to happen in the business.”

And although Papa George's pressure effectively terminated their romance - “From the day that my father took a shot at Bobby at the CBS studios during the Jackie Gleason Show, Bobby reconsidered our relationship,” is how she jokingly prefers to describe the event - his was still a major musical influence. She had long been impressed with the way he had switched from teen material like Queen of the Hop and Dream Lover to Mack the Knife, and shared his enthusiasm for the latter title's arranger, Richard (Dick) Wess. Wistfully, she recalls: “Bobby believed very much in Dick and after `Mack The Knife’ told me 'I've found the arranger for you if you want to do a hip album'.“

The “hip” album, on which Darin had helped rehearse Connie by playing piano and singing so that she could adopt his manner of phrasing, was 'Songs To A Swinging Band'. Recorded between October 11-13 in New York, the dozen sophisticated standards, among them Love Is Where You Find It, Swanee, I Got Lost In His Arms, How Long Has This Been Going On? and You're Nobody ’Til Somebody Loves You, remains one of the few representations of her own work that she will play. Its release coincided with the opening of `Where The Boys Are’, and featured a cover shot similar to Connie’s major musical sequence in the movie, but these plus factors were to no avail, and the album’s lack of chart action was a big disappointment to her.

Five days after completion of `Songs To A Swinging Band’ Connie was back in the studios for a session that produced three worldwide smash hits. The first of these was Where The Boys Are, of which she had already cut two soundtrack versions for the movie’s opening and closing credits sequences and, but for her determination, she might never have recorded either this million-seller (highest US chart placing #4) or the French, German, Italian, Japanese and Spanish versions which were to top the charts in 19 countries simultaneously.

While working on the `Where The Boys Are’ movie, film company parent, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, discovered what MGM Records had long realised, that Connie Francis was a young lady who was musically in charge of her own career. On learning that established filmland songwriting talents like Oscar winners Sammy Cahn, James Van Heusen and Paul Francis Webster were being commissioned to write a title song for the motion picture,

she advised producer Joe Pasternak that no team was more certain of producing a hit song for her than that of Sedaka-Greenfield.

She recalls: “I called Howie and Neil and said: `Guess what? You two guys are going to write your first title song for a motion picture,’ `What’s it about?’ asked Howie. `What’s the difference?’ `Well then give me the title.’ When I told Howie it was `Where The Boys Are’ he said: `That’s impossible. Call it `Where Are The Boys’, and maybe...’ But since the movie was based on a Top 10 book, we were stuck with the title and I told him `Just write the song and get it on a plane!’.

“The following week there were tons of songs called `Where The Boys Are’ and I received my package from Howie. Inside were two different versions of ‘their’ `Where The Boys Are’. One we all loved; the other we hated. At a meeting of all involved in the production production that I attended with Joe Pasternak, I played them the first version and they immediately said: `We’re sorry, Connie...You were right. Your friends ‘do’ know how to write a hit song.’ I said: `Please don’t say that, because this is the better song,’ and played the second version. They said `No, we like the first one.’ I said `Please, there’s no comparison.’

“I then called Howie and Neil and said: `I've got good news and I've got bad news. The good news is that you've written the title song for my movie. The bad news is that it's not the great version’.” The one preferred by Connie, Neil and Howie was never recorded, nor, inexplicably, was Turn On The Sunshine, also written by Sedaka and Greenfield and the only song actually performed by her in the movie.

Also stemming from her October 18 session were the previously unreleased On The Outside Looking In and Happy New Year Baby (which remained unissued until 1987), both from the prolific pens of Sedaka and Greenfield, a German version of My Heart Has A Mind Of Its Own (So Wie Es Damals War) and Many Tears Ago, the follow-up single to Where The Boys Are that, despite worldwide sales in excess of one million (it peaked at #7 in the US), at 1:53 remains Connie’s shortest hit (!).

According to Connie, shortly after recording Many Tears Ago, “My father played me Al Jolson’s `Are You Lonesome Tonight?’ and said `How about this for your next single?’. I listened and said `It's a smash’. For once we had agreed. I called Don Costa to ask him to book the studio, and arranged for a taped copy of the Jolson disc to be sent to him. About three days later we're on our way to the city to do the session when I hear the radio announcer introduce Elvis's new release, `Are You Lonesome Tonight?’. I just said 'I don't believe it!’. [NOTE: Connie eventually recorded the song some 29 years later!]

In her autobiography, Connie assigns chapters the titles of songs with which she is associated. One such chapter, `Breakin’ In A Brand New Broken Heart’, is named after her final October 18 recording and recounts the breakup of her relationship with Bobby Darin. The last she had seen of him had been when her father had threatened him with a gun during rehearsals for the `Jackie Gleason Show’. The incident had shaken her and, in her own words, “contributed to the most pathetic and embarrassing live TV show I’ve ever done. I simply forgot the words - all of the words!”

After the broadcast, the words she needed were those of comfort, and in her book she describes the telephone conversation she had with Bobby while still at the theatre. Bobby had said `Years from now, when you’re a big star and no one can ever touch you or hurt you again, you’ll laugh about everything that happened today. Someday when we’re both very, very old, we’ll laugh about it together - you’ll see. In this vast world, sweetheart, who loves you?’ He never called her again.

Country-tinged and written by Greenfield and Keller in the style of My Heart Has A Mind Of Its Own, adjectives used by reviewers to describe her performance on Breakin’ In A Brand New Broken Heart have included “moving”, “heart-wrenching” and “exquisite”. Connie’s account of events before the session adds additional pathos to the haunting quality of her voice on this wonderful recording that ‘Billboard’ crested at #7 and ‘Cashbox’ #5..

No less poignant is the way she ends this particular chapter by describing 9:55 AM on December 1, 1960 as a “moment frozen in time”. That was what the big clock on the entrance to the Lincoln Tunnel said when she heard the voice on her car radio announce: “Entertainer Bobby Darin and motion picture actress Sandra Dee were married earlier this morning by a Newark magistrate...”

That very evening Connie Francis made her debut at New York’s Copacabana, at 21 the youngest artist ever to appear at the Jules Podell showcase. Unlike the night of the `Jackie Gleason Show’, the last time she had seen Bobby, she remained in control, delivering an act which, as well as featuring the inevitable hits, Italian and Jewish material, also included numbers on which he had coached her. Her recorded performance was subsequently released on the album `Connie At The Copa’, housed in a jacket whose liner proudly displayed some of the superlative reviews she had received. A selection of them reads: “Connie wows them...Connie Francis made it - but BIG. Make no mistake about it - this girl is great!” - (Nick Lapole, ‘New York Journal-American’); “Connie Francis in her first Copa engagement is nothing short of sensational” - (Louis Sobol, ‘New York Journal-American’); “Connie’s big moment in her rocketing career... sensational supper club bow as a major star.” - (Frank Farrell, ‘World-Telegram & Sun’).

Whether it was the anguish she still felt at losing Bobby, or defensive qualities at play, there can be no denying that Connie's December 27 angst-laden third working of Pomus and Shuman's No One hit the mark. She had confidence in the song from the outset and, although this powerful vocal was assigned B-side status to Where The Boys Are in the U.S (and many other territories), it reached #34 in the charts in its own right. That same session was responsible for two more Sedaka-Greenfield tunes: the never-before-released Without Your Love, similarly suggestive of having been inspired by Connie's emotions at the time, and Baby Roo, a double-tracked novelty rock item not dissimilar to Stupid Cupid in construction, that provided the flip to Where The Boys Are in Britain. Completing that studio visit is Auf Wiederseh'n, a mournful updating of the Vera Lynn 1952 US #1. Possibly recorded at this session was One Tear Too Many, for which, despite exhaustive research, no additional information has been gleaned.

An extraordinary year for Connie, albeit one of contrast between personal and public lives, ended on a high on New Year's Eve with the well received Radio City Music Hall premiere of 'Where The Boys Are'. Later, she was awarded the “Laurel” by the film industry publication `The Exhibitor’ for “Best Newcomer to Motion Pictures and `Photoplay’’s first Gold Medal for “Best Female Singer of the Year”. Today Connie laughingly self-deprecates her performance and claims “It was my `Gone With the Wind’. It was all downhill after that!”

Her first 1961 recording session on January 31 kicked off with a revival of the vintage Let The Rest Of The World Go By. Adopting a much softer vocal style than that employed on many of her `belting‘ reworkings of standards, it found itself in competition for release with Breakin' In A Brand New Broken Heart which was still in the pipeline, and became yet another excellent performance to remain in the vaults. Someone Else's Boy, however, fared considerably better. The first song to be published by Connie's newly set-up Francon Music, it was first released as the B-side to Breakin' In A Brand New Broken Heart, but clearly too worthy an item to endure such relegation, was subsequently elevated to international status. As well as recording it in her `regular’ foreign translations of French, German, Italian, Spanish and Japanese, it became the first of her titles to undergo similar treatment in Dutch and Portuguese! The German and Japanese versions, in particular, were outstandingly successful.

Claimed to have been Most Programmed Artist on US radio in 1960, Europe’s Radio Luxembourg declared Connie that continent’s most popular recording artist of the same period and awarded her the Golden Lion, requesting that she record an item suitable for playing at the end of each day’s broadcast. The result was It’s Time To Say Goodnight, completed at a special session held on March 9 at the EMI Abbey Road studio. Feared lost for over 30 years, and only discovered during final research and checks on this collection, there are two quite separate versions, described as short and long; the longer featuring an extra orchestral passage and used by the station in the event of the final programme underrunning. Adding further suitability to the choice of this transmission `ender’ is the spoken passage in which Connie bids listeners “good night” in every popular European tongue.

When it was announced that Connie Francis was to be one of the artists performing the five nominees competing for the 1960 “Best Song” Oscar, she was immediately offered the sophisticated hot favorite, James Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn’s The Second Time Around (from ‘High Time’). She, however, preferred to identify with the provocative outsider Never On Sunday (from film of same name), and on April 17 found herself singing the winning song to a multi-million television audience. An impossible schedule of overseas trips, foreign language overdubs and spring issue of Breakin’ In A Brand New Broken Heart - it had charted that very week! - were all factors precluding her from recording and rush-releasing her own version of Never On Sunday at this time. The Chordettes took their recording of it to #13. Laying odds on a top 5 Connie Francis placing would have proved to be a very short-priced affair!

In May she made a triumphant return to the Copacabana where her diverse programme of songs brought rich praise from Milton Esterow of the `The New York Times’. “Miss Francis has warmth, some of the exuberance of Dinah Shore and the heartpulling power of Judy Garland,” he wrote. “So hail to the queen!” The venue was to witness regularly similarly received engagements by her over the next 10 years.

By late spring the decision had been made not to release Let The Rest Of The World Go By on a single, and at a three-song New York session on June 2 she cut the similarly gentle DeSylva-Brown-Henderson classic Together as her next release. Clearly inspired by the afore-mentioned Are You Lonesome Tonight?, a little known fact is that an uncredited Connie wrote the recitation which forms an integral part of this track, two variations of which exist. It had always been wrongly assumed that the mono June single contained the original recitation, and that a stereo recording, issued the following year, featured a re-recorded passage. Examination on digital transfer indicates that it is the million-selling single (it peaked at #6) which features an edited in narration. Preceding Together on this recording date was Too Many Rules, with which it had been coupled on the single, and Your Love, an English working of the traditional La Paloma. Connie's subsequent French adaptation, Jamais, would provide her breakthrough in that language.

Retaining the services of arranger/conductor Cliff Parman, Connie flew to Nashville that summer where during an intensive series of sessions that was to produce three albums and a single, she would record her own overdue version of Never On Sunday. On August 8 and 9 she cut 12 traditional titles for release on the LP `Connie Francis Sings Folk Song Favorites’, and on August 10 and 11 a similar number of tunes under the banner `Connie Francis Sings “'Never On Sunday” & Other Title Songs From Motion Pictures’. Included in the movie set were new workings of Young At Heart and April Love, each of which had, in 1959, been recorded as part of an aborted `One For The Boys’ album project. On both these LPs Connie was backed by The Jordanaires, with whom she also cut 10 titles that were sub-licensed to Mati-Mor Records. Although no specific August date has been determined for these tracks, it seems likely that they were cut before the MGM material since a) on August 12 Connie was in the studios without the Jordanaires and b) release of this set had to take effect by September 13.

The Mati-Mor set, containing folksy material as opposed to folk, as titled `Brylcreem Presents Sing Along With Connie Francis’ and licensed to the label to tie-in with her September 13 ABC-TV special sponsored by the men's hairdressing product. Aided by commercials for the recording during the broadcast, the album was an instant best-seller, albeit ineligible to qualify for chart placings.

Connie's final Nashville session was held on August 12, at which she cut three John D Loudermilk titles: the offbeat mid-tempo Hollywood, (He's My) Dreamboat, featuring the great blues sax sound of Boots Randolph, and novelty He's Just A Scientist, which remained unissued until 1987. Hollywood and Dreamboat formed her next U.S. 45rpm release but, although collectively the single sold very well indeed, radio play was split and individual chart identification for each title resulted in (He's My) Dreamboat peaking at #14 and Hollywood at #42. In Britain, where there was already a delayed release schedule and successful chart run by Together, the coupling was passed over. A fourth title cut on that date was Pretty Little Baby which, despite a belated Stateside appearance as an album track and British single B-side a year later, went on to become one of her biggest international successes via subsequent Japanese, Italian, French and Spanish versions. It was also the first title Connie experimentally selected for translation into Swedish!

Four days later, back home in New Jersey, she was the subject of CBS-TV's `Person to Person’, she appeared as mystery guest on that same network's `What's My Line’ broadcast from New York, and also found time to fly across the Atlantic to again top the bill on `Sunday Night at the London Palladium’.

In October, as `Never On Sunday’ hit the album charts (it peaked at #11), she heard a new movie song, When The Girl In Your Arms (Is The Girl In Your Heart featured by Cliff Richard in his film `The Young Ones’. She changed “Girl” to “Boy” and on November 2 it was the second of four titles to be recorded with Don Costa, and the one to place her back in the top 10. While it provided her with an upsurge in U.S. chart fortunes, it proved a costly error of judgment in Britain, since not only had Richard reached #2 with his version, but news of Connie's U.S. “cover” had met with adverse reaction from the music press as well as from Cliff himself who had been hoping for a Stateside breakthrough with the song. MGM chose instead to accord “A” status to When The Boy’s flip, the seasonal title, Baby's First Christmas, which virtually guaranteed a short-lived chart run. In the US, however, it provided her with yet another double-sided hit and reached #26.

Baby's First Christmas had been written by Benny Davis and Ted Murry about whom Connie has a favorite story to recount. “My father came to me one day and said: `I met two guys for lunch who've got a great song for you.’ `Everybody comes in with great songs. Have you heard this song?’ `No, I haven't heard it yet.’ `So how d’you know it's great?’ “I then added: `Incidentally, I hope they're young and know the market. I don't want to be embarrassed.’ `They're about 78!’ `Daddy, why are you doing this to me?’ `Only because they wrote `There Goes My Heart’, `Baby Face’, `I'm Nobody's Baby’. Shall I go on into the next century?’ `But that was a different kind of music.’ “He said `This is your music, and played `Don't Break The Heart That Loves You’.”

Connie was no stranger to Davis's lyrics, for it was he who had provided the words for her British #1 Carolina Moon, and now, with their paths having crossed once again, she went into the studio to record what in March 1962 would become her third US chart-topper. Completing her trio of Davis-Murry compositions was I'm Falling In Love With You Tonight, with which Baby's First Christmas was coupled in England.

Exactly one week later on November 9, she recorded White Cliffs Of Dover, another song originally popularised by British singer Vera Lynn. It lay dormant for 20 years, and a further 15 years on is accompanied by a hitherto unavailable alternate take on this collection.

Connie's final English language session of 1961 on November 20 was to have been a token acknowledgement of a dance fad started by Chubby Checker and his 1960 #1 The Twist. When recording Mr Twister, she could not have foreseen that a revival of Checker's disc would establish him as the only artist to top the U.S. charts twice with the same record, and make the dance even more popular. Seven weeks later she would return to the studio to cut an entire album of similar material. The Twist's renewed popularity also prompted Italian, Spanish and Japanese versions but, despite its pedigree of having been co-written by Don Mercy, Mercy Covay, the track was by-passed for singles release in the U.S. and played second fiddle to Don't Break The Heart That Loves You in Germany and Don't Cry On My Shoulder in Britain.

Also given the singles B-side treatment was Connie's first recording of 1962, Ain't That Better Baby?, another track to be included on the forthcoming Twist album. From that same session came Don't Cry On My Shoulder, a highly melodic double-tracked offering that gained limited release but which, for reasons best known to themselves, then British MGM licensees EMl Records sabotaged by prematurely fading out the second chorus, and the unreleased Love Bird, another Twist album contender.

On January 8 and 9 Connie was back at the studio armed with 13 Twist-oriented selections - 11 of them, like Love Bird, written by Eddie Curtis who in 1959 had supplied her with one of the best titles of her early career in the blues-tinged You're Gonna Miss Me. Infectiously and rhythmically arranged by Sammy Lowe, the tracks were easily among the best things she had attempted in the rock genre, and entirely due to the sassiness of her performances, the non-white feel on some of the more suggestive titles - e.g. Lovey-Dovey Twist and Telephone Lover - and the overall 'sound' of the production. As desirous as she was to tackle material with a little more bite, Connie decided against including Lovey-Dovey Twist, which like Cha Cha Twist is now released for the first time. The first title cut at these sessions, Gonna Git That Man, did not make it to the `Do The Twist With Connie Francis’ album and, like Ain't That Better Baby? before it, wasted on being relegated to the B-side of Second Hand Love. Although two versions of this track were released, mono pressings are, in fact, merely an abbreviated form of the stereo master. Tastelessly housed in plain black sleeve with fluorescent lettering on rush-release, the set was subsequently repackaged and retitled `Connie Francis Dance Party’ following the dance craze's demise.

The proven excellent quality of her early 1962 voice was next heard to outstanding effect on `Connie Francis Sings Irish Favorites’. The most underrated of any of her `ethnic’ collections, the January 25 and 26 sessions with Don Costa arranging and conducting, were held in an old, high-ceilinged church helping to create the voluminous but pure sound. The album, justifiably, is another of Connie's preferred examples of her work but, unlike the collections devoted to other well-represented groups in American society - Italian, Jewish and Spanish - neither created chart activity nor international stock catalogue recognition.

Voice control, pitch, power, tenderness, pathos, humour and drama are just some of the elements to be found on this collection, added to which is the début appearance of When Johnny Comes Marching Home. The only `traditional’ Irish tune cut by her, it is believed to have formed part of the January 8/9 sessions. Sadly, despite the existence of backing tracks and Connie's own session notes suggested she may have recorded two further Irish songs, Galway Bay and Peg O' My Heart, no vocals to these have been discovered.

On March 22, Connie held the first of two sessions at New York's A&R studios which produced a varied assortment of material that opened with the dramatic (and surprisingly unreleased) I'm So Alone. She subsequently achieved international success with her Italian (Io Sola Andrò) and Spanish (Que Sola Estoy) versions. New York columnist Earl Wilson provided the lyrics for the bouncy It Happened Last Night, and the by-now regular Francon Music contributors Davis and Murry were responsible for the sing-along styled No One Ever Sends Me Roses. The version included here is one not previously issued and to which, two years later, Connie would record a new lead vocal and harmony voice.

Three days later she was back at A&R for an intriguing session that kicked off with the country-style I Was Such A Fool (To Fall In Love With You), co-written by Mike Canosa who had done such a fine job of providing lyrics for her Kiss ’n’ Twist adaptation of the traditional Italian favorite Tarantella. On June 19, Connie re-recorded her introduction. Effectively placed over that of March 25, the true original recording is now lost. The one other title cut at this time was Second Hand Love, composed by Hank Hunter and Phil Spector, who happened to be closely associated with Herb Abramson, co-founder of Atlantic Records, and owner of A&R. This top 10 recording (it reached #7), is alleged to feature either Spector or Floyd Cramer on piano and though Connie’s vocals were laid at A&R, the backings, assumedly, were from Nashville.

At the time of Second Hand Love Southerner Cramer, who can be heard on Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel, had already had million-selling chart-topping hits with Last Date and On The Rebound, and was voted by disc jockeys the 1961 ‘Favorite and Most Played Solo Instrumentalist’. If Cramer ‘did’ take part, he almost certainly applied his skill on the ivories in the Tennessee town. Spector, soon to be a true giant of the business, was no less distinguished. A #1 gold disc for the self-penned To Know Him Is To Love Him, by the Teddy Bears, of which he was a member, he co-wrote, (with Jerry Lieber & Mike Stoller) and assisted on the production of, Ben E King’s Spanish Harlem. Yet another famed Brill Building songsmith, he had one year earlier launched his own Phillies record label with the Crystals and Oh Yeah, Maybe Baby, and was just months away from producing that group’s #1 He’s A Rebel. In Spector’s case in particular, the enigma is: ‘If he performed the honors, or took any part in the production of what eventually became a global million seller, why no further liaison?’

The final recording dates covered by this retroactive survey of Connie in the early Sixties are those from April 26-28 held at the RCA Italiana Studio in Rome. The sessions reunited her with producer Norman Newell and arranger/conductor Geoff Love with whom she had worked in London on March 9, 1961 to create It's Time To Say Goodnight. Assembled were 13 titles for an album under the working title of `Connie Francis Sings “Moon River” and Other Academy Award Winners’. Every one a proven winner, each of them familiar, the collection resulted in her most adult album of varied material since `Songs To A Swinging Band’. By the time she recorded the set, the 1962 ceremony for the presentation of the Oscars of ’61 had come and gone, and it was decided to hold back the album's release.

Twelve months later, in March 1963, on confirmation of the new Best Song Oscar winner, Connie recorded that title (Days Of Wine and Roses), and fresh instrumental backings were added to her 1962 vocals. The set was retitled `Connie Francis Sings Award Winning Motion Picture Hits’, Buttons And Bows, (to which no new backing was added) was dropped, and the revised 13-song compilation released in the April. Unexplained, however, is ''the tape that got away''. Both Australia and New Zealand were inadvertently supplied with album masters featuring the original Geoff Love orchestrations, now deliberately and expressly released for the first time in their entirety.

By April 1962 Connie Francis was established as the world's most successful female recording artist, her music touching millions. In her autobiography there are many quotes to summarise how she felt and feels about her achievements. None, surely, could be as apt as the following:

“I ‘am’ my work! What - ‘who’ - would I be without it? It's the very best part of me - or anyone else for that matter. It's a reflection of everything you are. And besides, your work is the only thing in life that truly belongs to you. Not a person in the world can ever take it away from you.”

RON ROBERTS

London, March 1996